Republic

Book Publishers

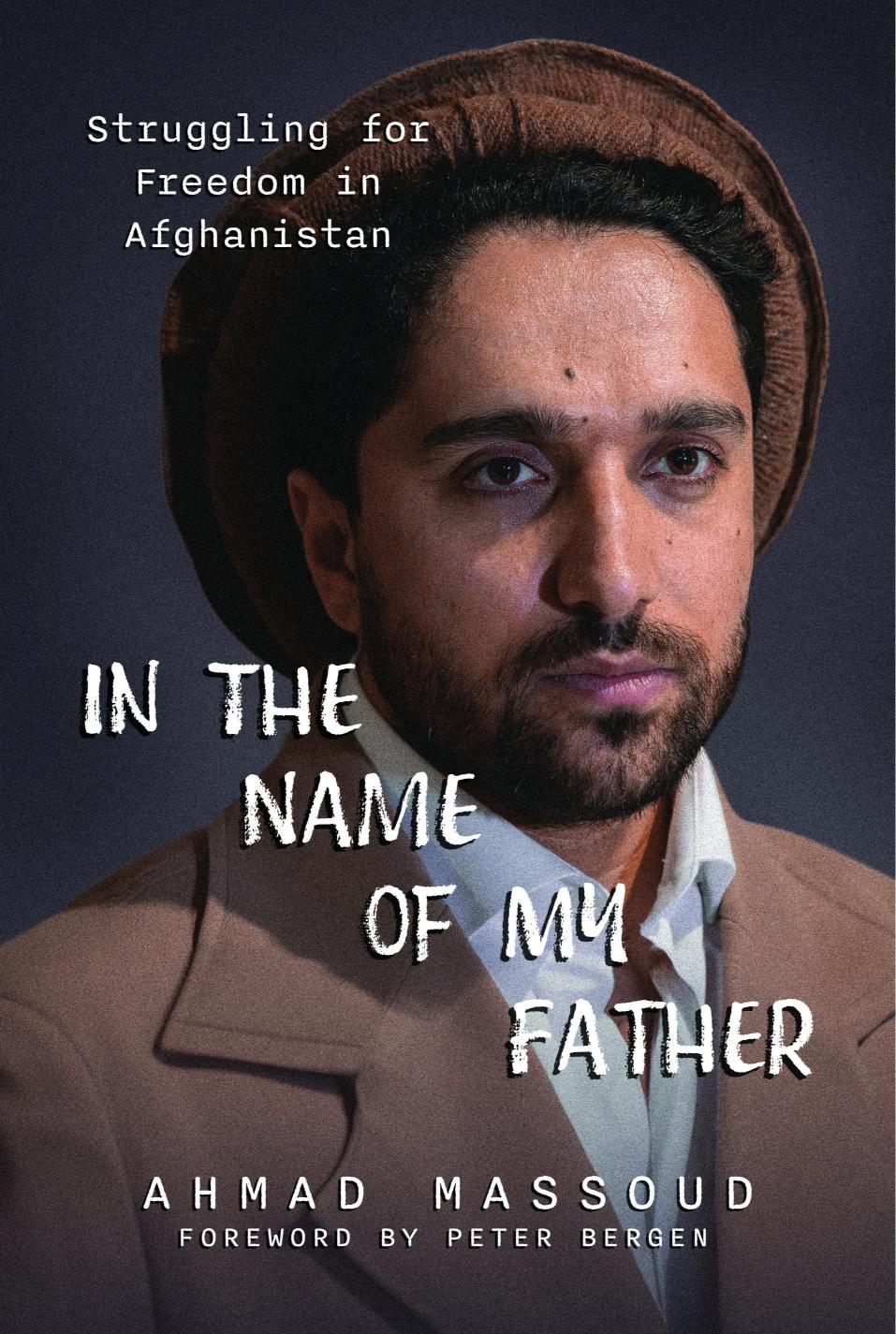

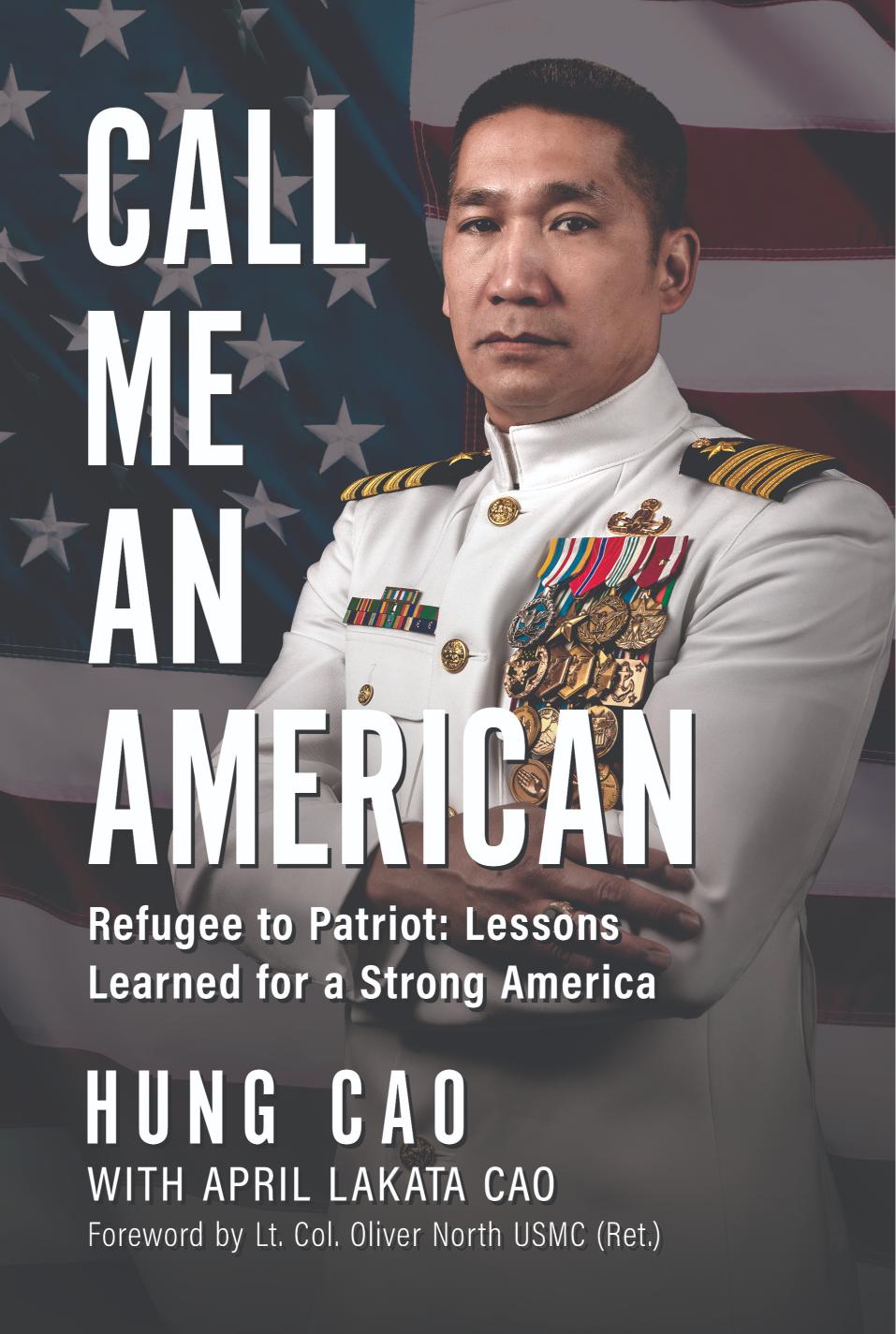

We amplify First Principles through the publishing of books and showcasing authors

and their ideas using a unique communications and marketing model to re-engage the public

in America’s founding ideals

Coming Spring 2024!

To be added to our collection

All of Our books are available anywhere books are sold, including Amazon, Barnes & Noble, other online sales outlets and all bookstores. In addition, you may purchase our books directly from Republic, here at member discounts.

Reserve Your Copy Now

Start Saving today on book purchases!

BECOME A MEMBER

Become a member of Republic Books to get up to 40% discount on our titles. Membership will also give you priority invitations to author and speaker events as well as additional discounts on tickets.

Your membership also enables you to stay abreast of articles and trends in today’s new conservative movement.

FOR AUTHORS

Republic Books partners with our selected authors to better showcase their books and their ideas through extensive PR and multi-media exposure.

TESTIMONIALS

We are proud of our history of delivering outstanding results through our services. See what some of our clients have shared about their experience with our work.